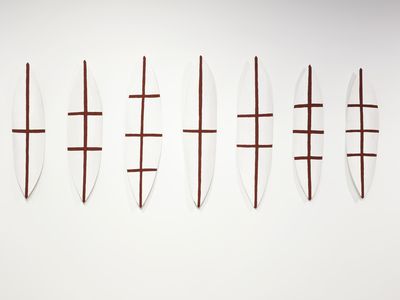

Michael McDaniel

Badhang wilay (possum skin cloak)

2005

pokerwork on sewn brushtail possum skins

120 x 210 cm

Located on level 6 of the UTS Tower building, near the entrance to Jumbunna [CB01.06]

The making and wearing of badhang wilay, pieced together from Brushtail possum pelts, is a traditional practice with strong emotional and spiritual resonance for Aboriginal people from South Eastern Australia. The cured skins are embellished with pokerwork designs that speak of the status, place, and identity of the wearer.

Only a handful of possum skin cloaks made prior to 1900 still exist today, preserved in museum collections held in Australia and overseas.The scarcity of old cloaks is due both to their fragility and purpose; they were designed to be used during the lifetime of their owner and often as a burial wrapping.[1]

This possum skin cloak was made for Aunty Joan Tranter by Emeritus Professor Michael McDaniel, while she was the inaugural Elder in Residence at UTS. In recent years, the practice of possum skin cloak making has re-emerged as an important practice for Aboriginal people in south-eastern Australia. Emeritus Professor McDaniel, a member of the Kalari Clan of the Wiradjuri Nation of Central New South Wales, has been one of these contemporary practitioners with a commitment to the preservation and teaching of cloak-making, with the encouragement and approval of Wiradjuri elders. Rather than taking the skins of local possums (now a protected species in Australia) skins are sourced from New Zealand where the Australian brushtail is regarded as a pest species.

Once an everyday item for Aboriginal people in south-eastern Australia, possum skin cloaks were worn for warmth, used as baby carriers, coverings at night, drums in ceremony and for burial. Worn from a young age, cloaks started out small with a few skins sewn together to wrap a baby. Over time, more skins were added so that as a person grew, their cloaks grew with them.[2]

For Emeritus Professor McDaniel, the making and wearing of these cloaks in formal and ceremonial settings is a sign of real progress towards mutual acceptance by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples of the strong connections between culture and country, recognition and respect, and a visible and tangible connection to Aboriginal people’s own stories and histories. This cloak was donated to UTS by Aunty Joan Tranter upon her retirement, and is displayed alongside her portrait outside the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research.

[1] "Possum skin cloak", https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/possum-skin-cloak

[2] "Possum skin cloak", https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/possum-skin-cloak

Emeritus Professor Michael McDaniel is a member of the Kalari Clan of the Wiradjuri Nation of Central New South Wales with a distinguished career in Indigenous higher education and record of service to the arts, culture and the community spanning more than three decades.

To wear a possum-skin cloak has an impact on you, physically, emotionally, psychologically and spiritually, that I have never seen another object have. In some ways I would say there’s a spirit in them. I believe these are sacred things. But they’re not sacred things as in the western sense where they’re not part of everyday life. These sacred things are everyday things. They are powerful things. And I feel like they’ve come back to us at the right time.

/https://uts-art-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/media/dd/images/df377b6c21304ede1f1e8f14abd59915.jpg)