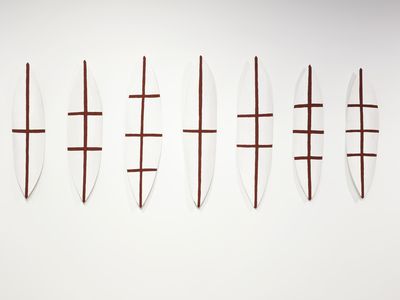

Tracey Moffatt

Up in the Sky

1997

offset prints

25 parts, each 96 x 108 cm

UTS Business School (Building 8), levels 3-4 [CB08.03-04]

Tracey Moffatt's Up In The Sky series is an oblique narrative of race, class, and violence set in an archetypal Australian town. Across 25 ‘frames’, the staged scenes in sepia and black and white recall any number of epic dramas—from the apocalyptic to the prosaic—albeit set in the dusty streets of Broken Hill with a local cast. As with many of Moffatt’s previous and later works, Up In The Sky eludes a single narrative interpretation or resolution. Instead, the series invites multiple interpretations and encourages return viewings.

In his specially commissioned essay on the series, writer, journalist, and radio broadcaster Daniel Browning writes:

To my mind, the banality of violence—ranging from the physical to the psychological, the interpersonal to the structural, whether racialised, gender-based or economic— is the subject of the series. The threat of violence is omnipresent in this place, the ‘Nowheresville’ of Moffatt’s imagination. Despite its title, the drama upon which Up In The Sky pivots is neither speculative nor dreamlike. The thread-like storylines dangled by the artist speak to faultlines in the national character: the genesis of the nation state in banal violence, performed along multiple frontiers by psychotic boundary riders and genocidal maniacs with naming rights.

UTS has held three prints from Up In The Sky since 1998. In 2023, a generous donation of 22 prints to UTS completed the series. Notably, full suites of the series are held in some of the most prestigious art collections in the world, including the Tate, London and the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Tracey Moffatt is one of Australia’s most renowned contemporary artists, both nationally and internationally. Working predominantly in photography and film, Moffatt is known as a wholly original visual storyteller whose works draw upon the narrative and stylistic languages of cinema, television, and media culture. Moffatt has held over 100 solo exhibitions of her work in Europe, the United States and Australia and, in 2017, was the first solo Indigenous artist to represent Australia at the 57th Venice Biennale.

Up In The Sky, (1997)

Tracey Moffatt

Daniel Browning

I flinch in recognition when I am confronted by certain images from Tracey Moffatt’s photographic series Up In The Sky, such is the banality of the (utterly identifiable) violence that unfolds in the suite of 25 monochromatic images. I say confronted, and deliberately so. That’s because, for me, these works trigger an embodied reaction: I flinch, I smart, I can’t look away. I feel as if I know these people: the nuns, the drunks, and the rednecks. Yet I am also drawn to the side notes, the apparently minor details; the hole in the fibro that haloes the sleeping child in #20, such as a balled fist would make. In #22, the camera zooms closer as if predating on the infant and at a slightly different angle, revealing another hole in the adjacent wall at the child’s feet. Clearly these are not minor details; they are counterposed by the utter vulnerability and innocence of the child who has lapsed into unconsciousness after a bottle feed in the heat of the day, literally guts up. We don’t need Moffatt to explain that the holes in the splintered fibro are signs of internal rot.

As if conducting an orchestra, Moffatt tunes the dramatic tension until the multi-story narrative reaches one of its climaxes in a fight sequence. Male bodies naked to the waist, writhing like coiled snakes. Except these bodies are locked in an existential struggle—that of the colony. In the iconic scene, the fight is shot from directly above: presumably with a fixed camera attached to a jib and remote shutter. The manoeuvre transforms the banal racialised violence that is the lived experience of every blackfella I know into something monumental, even classical. Somehow, what we are seeing is less of a struggle and more a balletic, choreographed dance echoing the frozen, tableau vivant sex scenes in Gus van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991).

To my mind, the banality of violence—ranging from the physical to the psychological, the interpersonal to the structural, whether racialised, gender-based or economic—is the subject of the series. The threat of violence is omnipresent in this place, the ‘Nowheresville’ of Moffatt’s imagination. Yet the location for the shoot—a perpetual frontier and one of Australia’s most visited historic inland towns, if not the most photographed and filmed after the success of Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981)—could never deliver the kind of anonymity the artist may have wanted. Nowheresville is instantly somewhere to me. I recognise everything from the saturated quality of the light, the amplitude of the pictorial space, the heat emanating from the copper tones of the wrecking yard to the fine grain of the sand that threatens to swallow the historic mining town, reclaiming it for the mulga and saltbush of Wilyakali country.

Despite its title, the drama upon which Up In The Sky pivots is neither speculative nor dreamlike. The thread-like storylines dangled by the artist speak to faultlines in the national character: the genesis of the nation state in banal violence, performed along multiple frontiers by psychotic boundary riders and genocidal maniacs with naming rights. A strange, twisted nightmare that lurches from zombie-like somnambulist masses in back laneways (#15) to an ageing, shock-haired exhibitionist wearing little else but a pair of sunglasses and a maniacal grin who flits around as if his mode of transport is the Tardis: Moffatt rearticulates as many tropes as she tries to strangulate and bury others.

The Bundjalung poet Evelyn Araluen might have been immersed in the plots and subplots of Moffatt’s epic when she wrote the following lines in her Stella Prize-winning debut Dropbear—a razor-sharp critique of the great Australian trope. “The trope neatly folds conflictual narratives of national subjectivities and external politics into aesthetic production…”[i] In her takedown, Araluen doesn’t spare any literary or film convention which personifies some longed-for national characteristic, while deluding itself about the blood staining the crime scene. A prompt to the reader, the final line of the prose poem is surgical: “The trope will meet you on the road. Kill him.”[ii]

Unquestionably, Moffatt’s psychologically complex unmade films, scenes and vignettes that live in our collective unconscious are infinitely more memorable, self-aware, and skilfully directed than many big budget features. Baz Luhrmann’s fatuous epic Australia was not far removed from the 1955 assimilationist film Jedda in its rearticulation of the noble savage. The broken glamour of Moffatt’s series, and indeed perhaps her entire body of work, speaks to the parochial, self-referential, and limited nature of Australian visual culture. Perhaps without knowing it, many have replicated Moffatt’s sense of space and the amplitude of the outback as a blank upon which to project national fantasies.

Tightly constructing the mis-en-scene of each of the 25 stills into a broken narrative which unfolds in a remote outpost—a blank ‘Nowheresville’ which might be the outback or Texas or Saskatoon—Moffatt draws our eye to several recurring motifs. The fight/colonial struggle plays out in several climactic scenes, broken by other stories as if intercut. The sleeping child of the two nearly identical images in the suite, #20 and #22, is used as a live prop elsewhere, most dramatically in #7 and #9, where Catholic nuns hold the child aloft to the sky. The effect is to imply that the baby is indeed the point of the drama we are witnessing. A few months after Moffatt photographed the series the National Enquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families delivered its findings in the 1997 Bringing Them Home report. The witness testimony heard by the national enquiry and subsequent media coverage produced a momentary bloodletting, answered politically—at first—by deaf silence. A statement of mere regret, declined, was all the former Prime Minister John Howard could manage. As much as the artist may want us to depersonalise our national trauma and see throughlines to universal human experience instead, the ensuing history wars and memory politics that came to define the conservative Howard era are part of the cultural context of Up In The Sky.

These 25 extraordinary images suspend a narrative that is unending, morphing with every viewer into more twisted variations of the story. Moffatt, the auteur, stages the entire drama as if storyboarding a film, which crosses the apocalyptic Mad Max—a vision of a quintessentially Australian dystopia where cars are weaponised—with the fifties glamour, Freudian sexual imagery and class warfare of Giant, and the horror of racialised trauma porn and blaxploitation. If you blink, you might see stills from an overcooked spaghetti western directed by Pasolini, starring identifiably Aboriginal characters—extras in Moffatt’s, or indeed my own, life.

[i] Araluen, E. (2021). Dropbear. University of Queensland Press.

[ii] Ibid.

Daniel Browning is a Bundjalung and Kullilli journalist, radio broadcaster, documentary maker, sound artist and writer. Currently, he is the Editor of Indigenous Radio with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and produces and presents The Art Show for ABC Radio National. He also presented Awaye! for many years on Radio National, surveying contemporary Indigenous cultural practice across the arts spectrum. His 2024 book of collected writing, Close to the Subject, won the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for Indigenous Writing.

/https://uts-art-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/media/dd/images/02e4cd61f03a160c71ac5afa967a498c.jpg)

/https://uts-art-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/media/dd/images/e13b96183e5209d5a0c51399ffeaa31d.jpg)

/https://uts-art-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/media/dd/images/00c7ff730a073ca9a6dd6aa34a23f2bb.jpg)