Badger Bates

Water is Life

2023

Linocut prints and wallpaper enlarged from linocut prints

dimensions variable

Located in Building 4, Level 4

(CB04.4)

Water is Life reflects how it has been for my people since white occupation. It has been a terrible drought for my people, physically and spiritually, but I can see our country is healing a bit and my people are healing with it. Our land and people are at last being given some respect and recognition, but we need to keep this happening, you can’t give up the struggle. I hope my artwork will help explain how important our country is to us Barkandji people and that we are the best ones to look after it.

— Badger Bates

Uncle Badger Bates is a Barkandji Elder whose practice as an artist, cultural heritage consultant and environmental activist incorporates the landforms, animals, plants, songs and stories of Barkandji Country and the Baaka (the Darling River). As such, his work cannot be thought of as art alone; it requires an understanding of the importance of the Baaka and efforts to protect it for his culture and sense of self.

This artwork, featuring Uncle Badger’s linocut prints and accompanied by his stories of the Baaka, has been commissioned by the UTS Faculty of Science to assist science students in their appreciation and understanding of Indigenous people’s connection to land, animals and water as part of the UTS Indigenous Graduate Attribute initiative.

Kularku Maarni, Brolga Dance 2023

Wallpaper enlarged from linocut print

Kularku (Brolga) is our relation, we have great respect for them, they are close family. They dance for us and teach us to dance. As they fly over us, they swoop down low and sing out to us, we sing out back. Of course, we don’t eat them. This picture is located at Toorale National Park, and the Kularku are dancing on the western floodplain, a kind of anabranch of Warrego River near its junction with the Baaka. Barkandji families from the Toorale area are working with the scientists and water managers to make sure the Kularku can continue to live and to nest here like they have forever. For them to thrive in this place they need enough water to support the right kind of plants with bulbs, and small fish, yabbies, shellfish, and insects to eat.

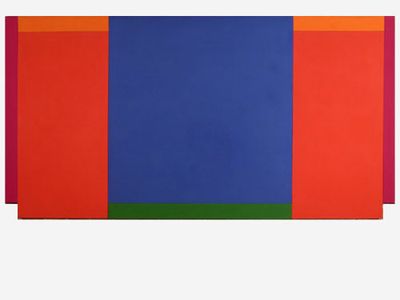

Menindee Fish Kills (2018-2019) 2023

Linocut print

In the summer of 2018-2019 millions of fish died in the Baaka at Menindee. Through the beautiful river and trees with ancient canoe and coolamon scars, you will see the skeletons of the fish that died at the end of 2018 and the dead and dying fish in early 2019. It was like a massacre, our people cried and cuddled the dying Parntu (cod), our ancestor and creator, it is us. The little Nhaampa (bony bream) are the totem of many Barkandji people, it was like family dying in front of you. The Kunpali (golden perch), Yamaka (catfish) and Pangula (black bream), our food and medicine, gasped for oxygen. The sky at the top of the print lights everything up, it is hope for the future.

Yungkuuli, Narran Lake Swans 2007

Wallpaper enlarged from linocut print

Years ago, many Yungkuuli (swans) were always at Narran Lake, it’s not in our country but we heard about it because it is a special place for the Uallaroi up that way. We usually didn’t eat the swans because they mate for life and if one dies the other one frets. At Wilcannia the eggs fed us when we were kids, we only take a couple from each nest. The Yuungkuli (swans) fly north-east towards Bourke to meet the floods coming down the river, we sit down in the night and listen for the swans, they tell us when there is a flood coming down.

Life Coming Back to Moon Lake, Wilcannia 2011

Linocut print

This print was made after the big drought broke in 2010-2011. I started carving this lino when Baaka, the Darling River, began to flood and filled Lake Woytchugga at Wilcannia. I thought about my childhood, how my old Grandmother with our old uncles and cousins would walk to Woytchugga and collect swan eggs, duck eggs, and other waterbird eggs from the lake, and also goannas, porcupines, kangaroos and emus from the sandhills.

The white people call it Lake Woytchugga, but the proper Barkandji name is Baaytyuka, which means moon. It belongs to the story about the boy in the moon. If you look at the outline of the lake, you will see the young boys face looking to the left. The first catfish nest closest to the left is the boy’s eye, and the one in the middle is the boy’s ears. The two catfish nests represent the reflection of the moon in the water as the moon moves across the sky.

I put the Darling Lilies down the bottom of the picture because the lily bulbs, or wild onion as us Barkandji people call them, lay under the ground for years waiting for the big rains and the country to flood to make them grow. Those plants and other plants and animals were under a lot of stress from the drought, just like us Barkandji people. The white flowers on the lily represent reflections of the moon on the water and the renewal of life on the floodplains after rain. The lilies represent the people because Barkandji people don’t pick the flowers, they have to be left where they grow because it is all part of us. The Yungkuuli (swan) nests and Yamaka (catfish) nests also represent life coming back to Lake Woytchugga and our country after the big drought. As the lake filled up, us Barkandji people kept coming out to look at the lake, people even cried they were so glad to see the water, the birds, the fish and everything.

Uncle Badger Bates is a Barkandji Elder whose practice as an artist, cultural heritage consultant and environmental activist incorporates the landforms, animals, plants, songs and stories of Barkandji Country and the Baaka (the Darling River). As such, his work cannot be thought of as art alone; it requires an understanding of the importance of the Baaka and efforts to protect it for his culture and sense of self.

/https://uts-art-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/media/dd/images/02e4cd61f03a160c71ac5afa967a498c.jpg)

/https://uts-art-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/media/dd/images/3b7814e97b4b5428c7efccb0692cb077.jpg)

/https://uts-art-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/media/dd/images/df377b6c21304ede1f1e8f14abd59915.jpg)